The History of our Raven Inn

Aka The History, Social History and Landscape Archaeology of the Raven Inn, Glazebury, Cheshire

The Raven Inn was put up for sale in 2019 for demolition and redevelopment. The advertising for the planned development included the lure: “Built on the site of the historic Raven Inn”.

This plan was, frankly, devastating for the local community who loved the landmark, its history and its once thriving environment. An action group was set up on Facebook to ‘Save the Raven’, which over the next three years attracted 1000 supporters.

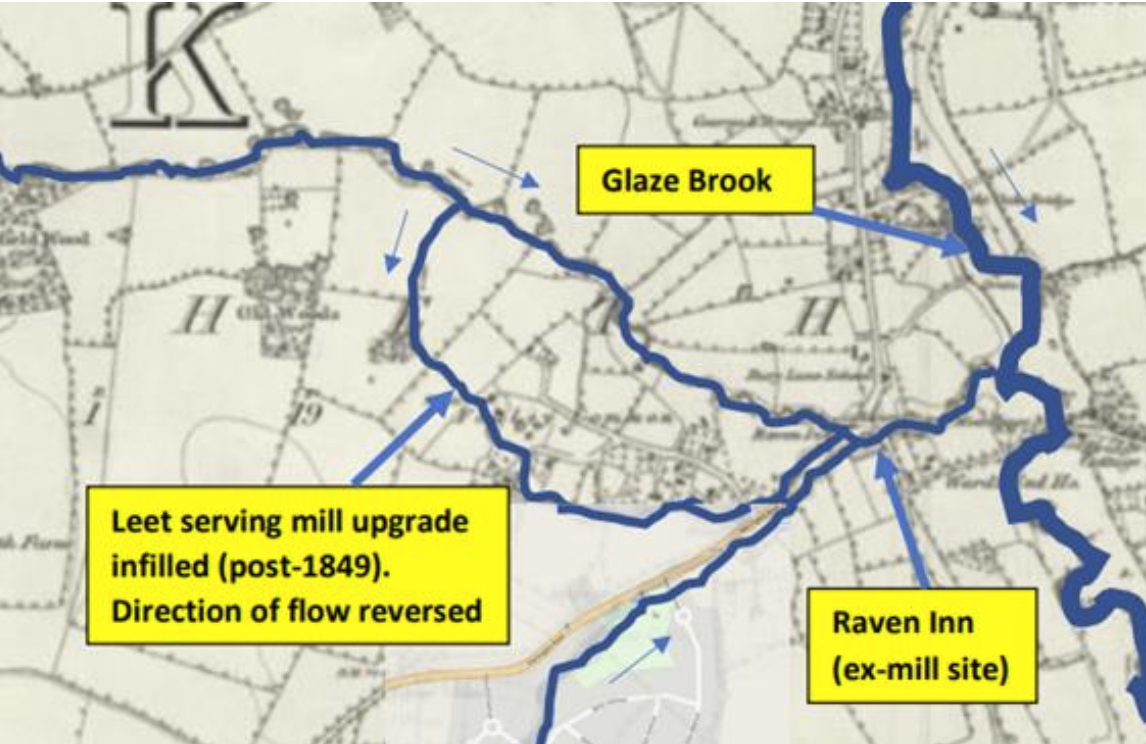

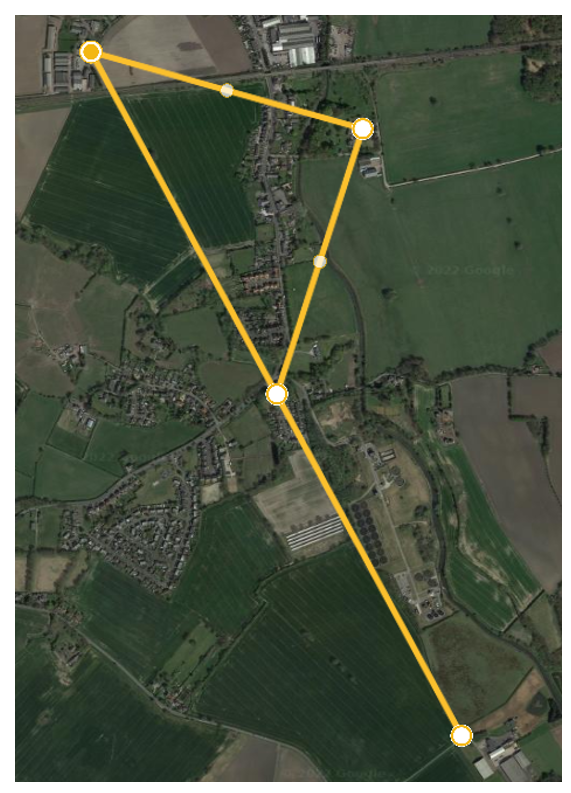

The first inkling that the Raven Inn was on the site of an ancient structure came when Facebook member, Arizonian historian Van Hostetler, identified that a ‘five furlong spacing’ existed between the medieval halls in a chain of halls along the Glaze Brook. The site of the Raven fell on a spacing between Holcroft Hall and Hurst Hall, which Van considered significant, alerting the ‘Save the Raven’ action group. This is the remarkable nature of the internet – an historian 5,000 miles from the inn could join the fight and participate on an equal footing with the local community.

Intrigued, scientist and amateur historian Bob Eden responded to a request from the ‘Save the Raven’ action group to investigate this ‘strange’ claim of Van’s. He did, with some initial scepticism, and it was the beginning of a trans-Atlantic collaboration lasting to this day.

Medieval Period

This layout is perhaps the ‘metes and bounds’ survey relating to the division of Gilbert’s estate.

Also from this point, a line to Light Oaks Hall and then 90degrees to Hurst Hall is 730m along each line. The line from Light Oaks Hall crosses the Glaze at its mid-point over Light Oaks bridge, which had sufficient bearing capacity to carry the weight of a hay wain and horses, adding to the likelihood of this interpretation of careful laying-out.

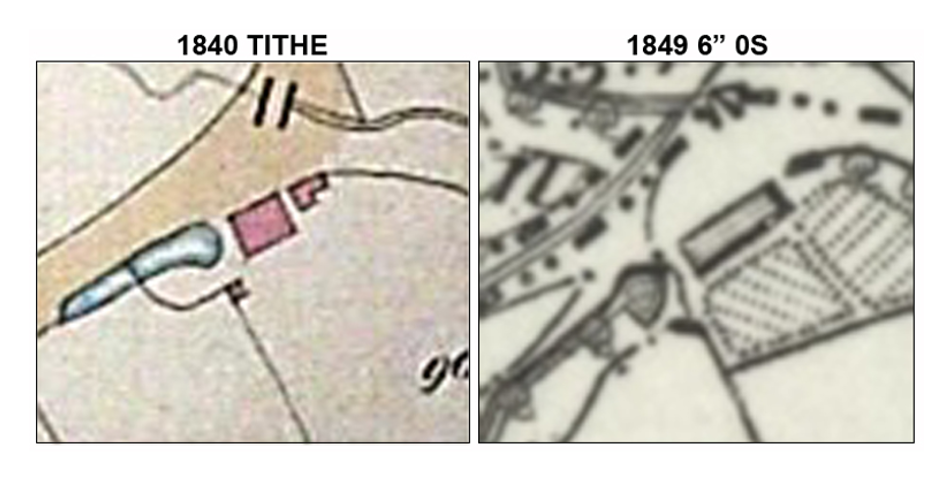

The track following the line to Holcroft today is known as Hey Shoot Lane, probably taking its name from middle English and French for the ‘high chute’ (as in water chute), namely the tailrace of the mill. Perhaps the track in the other direction over Fowley Common to Hurst Hall was the Lowe Shoot Lane? But this is conjecture.

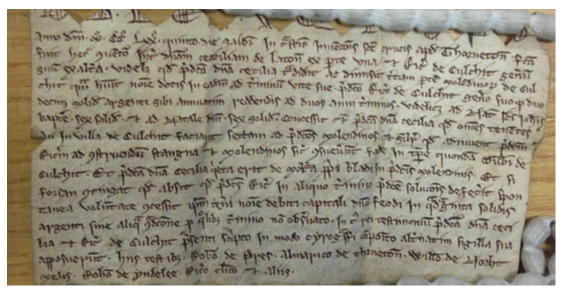

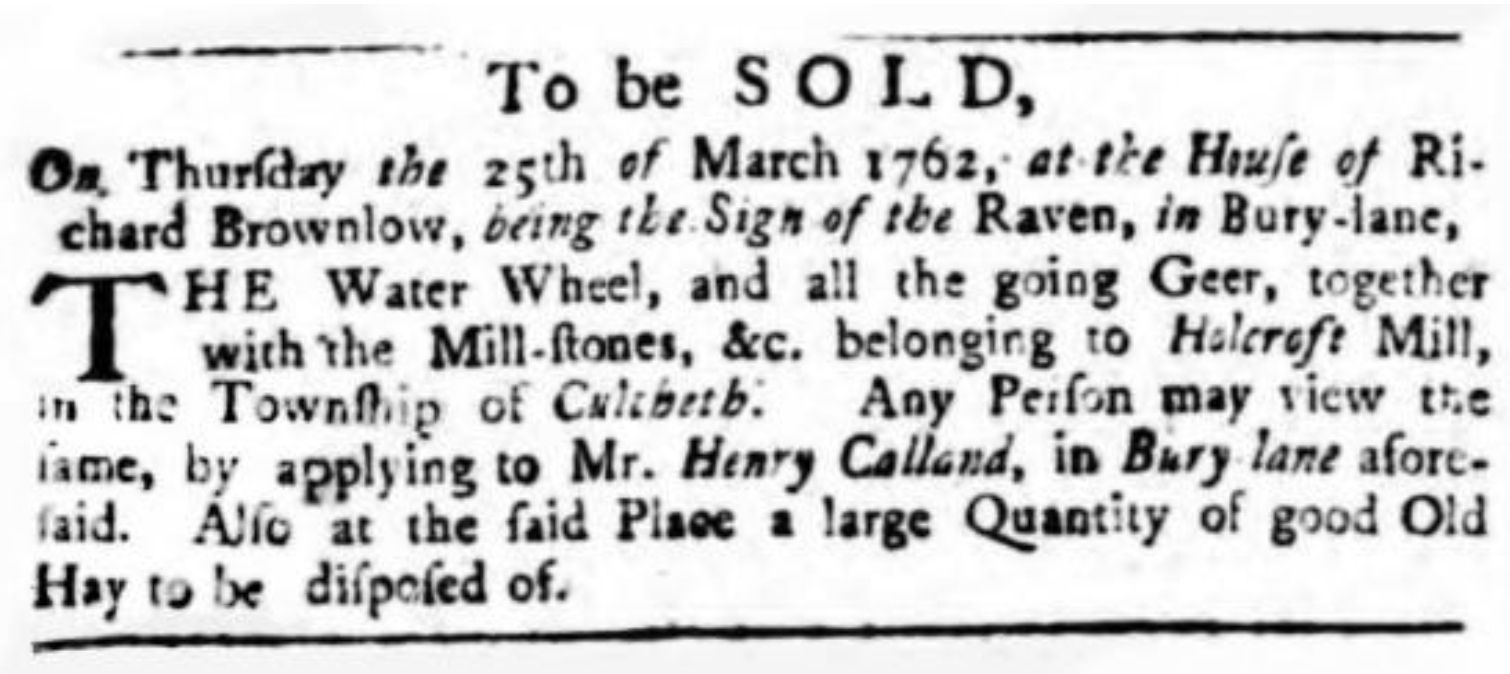

Here is one such mill reference from 1275:

In the year of our Lord one thousand twelve hundred and seventy-five on Saturday on the morrow of the Invention of the Holly Cross at Thorneton this agreement was made between Dame Cecilia de Lawton on the one part and Richard de Culchit/gentleman/ on the other. Namely that the foresaid Dame Cecilia leases and demises a third part of the mills of Culchit which she has in the name of dower in the same for the term of her life to the foresaid Richard de Culchit /gentleman/ for twelve shillings of money paid to her annually at two terms of the year namely at the Nativity of Saint John the Baptist six shillings and at the Nativity of our Lord six shillings. And the foresaid Dame Cecilia has granted that all the tenants in the township of Culchit shall do suit at the foresaid mills and similarly that the said Richard is to construct a new pond and mills as was customary in the time of Gilbert de Culchit. And the foresaid Dame Cecilia has the right to grind her own corn in the foresaid mills. (And continues by stating what happens if the rent is not paid etc together with the sealing and witness clause).